Hunting Wild Indigo

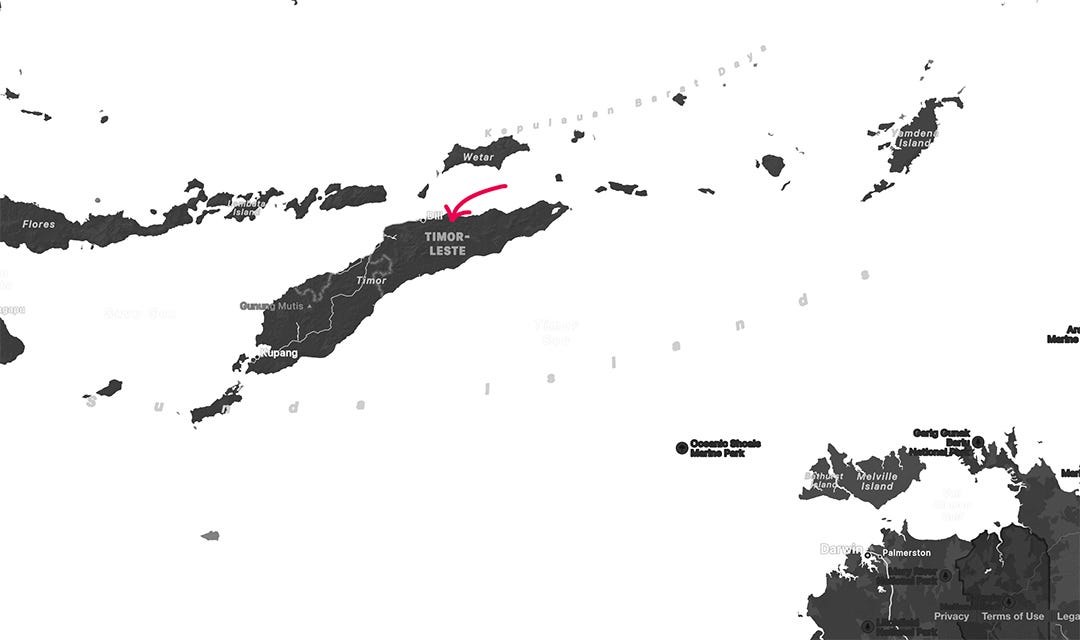

A journey in Timor-Leste to collect wild indigo

For me, the next creative adventure has begun.

(p.s. this post is too long for email, click through to see the full post or go to the Substack app)

I am here, in Reloka’s dye garden in the outskirts of Timor-Leste’s capital Dili.

And Mana Secilia is alight with anticipation.

She has spotted an abandoned rice paddy taken over by wild indigo in the neighboring district of Manatuto.Let’s get hold of a car on Friday and go and harvest it, she says.

Are you coming with us, mana Helen? (Mana means big sister, we all call each other mana or maun - big brother - here). Of course I will.

I am in Timor-Leste with my husband Alastair Gordon who is volunteering (through VSA) with a micro-finance group and I am volunteering with Reloka. Reloka is on a mission to both record traditional knowledge of plant dyes and to improve natural dying techniques here. Mana Secilia is their dye master.

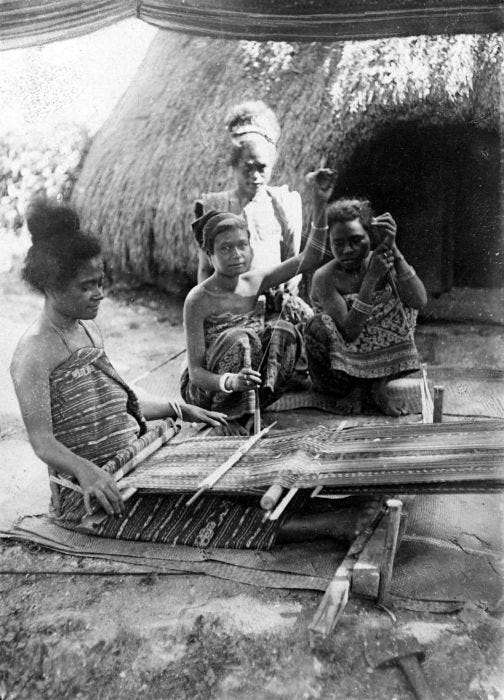

Plant dyes are used in the traditional weaving, called tais. Tais have long been the primary art form in Timor-Leste - so much so that the UN has recently declared Timorese tais an intangible treasure. But the knowledge of the dye plants used to colour the tais is close to being lost.

Disappearing knowledge

Resistance to the Indonesian occupation of Timor-Leste (from 1975-1999) was widespread and if a village was suspected of harbouring rebels, massacres were often the tragic ending.

The Timorese who are alive now are very often the ones who fled into the wild, dense mountain jungle and lived there (sometimes for years) hunting and foraging.

Many would return to their villages to find everyone killed.

In terms of cultural destruction, this was a double edged sword. While living in the jungle, they could not practice the more settled arts like weaving and dyeing. So practical experience was lost.

More than that, the chain of inherited knowledge was broken. Each family or kin group would have secret dyeing recipes, techniques, and rituals that would be passed down only from mother to daughter. But when the mother or daughter died from starvation or was killed before the knowledge could be transmitted, that chain was broken forever.

So industrially produced threads imported from Indonesia have taken over for tais weaving. The smooth, fine and brightly coloured industrial threads make vibrant, smooth and fine woven tais. They have become so popular that now the brilliantly coloured tais made from synthetic dyes are almost a defining mark of Timorese culture. The muted, earthy natural plant colours look dingy next to them. (Actually everything looks dingy next to the bright synthetically coloured tais).

A good article on tais by Sara Niner is here and a video showing the complete process of spinning, dyeing and weaving tais here

The journey

The Reloka Kor Natural team (Secilia, Julia, Hagai and Julia’s brother) set off and Mana Secilia spots the field of wild indigo. A rice paddy that has been left un-tended by an elderly couple has been taken over by Indigo tinctiforia. It looks, and grows, a bit like wild broom. The wild indigo stretches out over acres.

It is a delight to see this ‘blue gold’, the valuable source of clear, deep blue growing wild.

We chat to the old man who owns the fields. He is sitting by his stall on the side of the road, where he sells his farm produce, a rather laid back chap. Today he has one papaya only to sell in his stall.

Julia asks to buy it, but he wants $2 and Julia only wants to pay $1.

We tell him we are interested in his indigo and will be back later in the day, if he is amenable to us giving him some money to collect indigo leaves. He is indeed amenable, but surprised. He has no idea that this plant growing everywhere is anything other than a weed.

But we can’t do business with him about his indigo yet. We are visitors to this district, and it is very bad manners to just go into someone else’s district and walk around and do business without a proper invitation or permission.

Our first step is to find the village Xefi (chief - an elected position). We find him repairing the village road together with almost all the villagers. We have prepared an official letter, with the Reloka letterhead and properly signed and stamped, talking about the Reloka mission and why we want to collect indigo in this village. We hand the letter to his teenage daughter to read aloud and he gives us his consideration, and agrees to sign the letter.

We are not finished, because we need permission from the head of the larger sub-district too. So we drive off to find the administrative headquarters, where the Suko (sub-district) Xefi will be.

We take off our shoes and enter the verandah of the wonderfully blue Suko administration building. Some kind women greet us, give us seats and invite us to wait for the Xefi to return from church. We wait a very long time, chatting with the women, reading aloud our letters explaining why we want to be here.

No-one here uses indigo for dyeing, they tell us. In fact no-one realises it is a dye plant at all. Instead it is used as a medicine, the green leaves taken as an effective tonic. Like many dye plants, indigo is also full of medicinal compounds. No-one in the smaller village knew of it as a dye plant, either.

The Suko Xefi never comes back from church, so in the end we are given permission to carry on by the women who have been talking to us.

Negotiation

We return to visit the field of indigo, now that we have the permission to start negotiating. The stall has been stocked with a bit more produce since we left and the owner has been joined by his more assertive wife, who has heard that a group of people, including a ‘malae’ (foreigner) want to harvest the weed growing in their abandoned paddies.

She is energetically chewing the mildly addictive betel nut, popping nut after nut into her mouth with a speed I have not often seen here in Timor-Leste.

We open with an offer of $5 for the right to collect half of the plant leaves.

She responds with disbelief. I have expenses! she declares. I need to buy more betel-nut! It always running out and it’s not cheap, you know.

Also, she adds, you have a malae in your group. (That’s me, of course). If you have malae, she says, you have lots of money! Malae always have so much money, so that means you must be a rich group. The price is double, I need $10 for this. I’ll be able to get all the betel nut I need, this way.

She is completely determined, tough negotiator, so $10 it is.

I ask if I can take her photo. She wipes the bright red betel juice off her mouth and in an inspired bit of ad-hoc marketing, holds up a papaya to her face and smiles happily to the camera.

Julia comes to an agreement about the price of the papaya, and we go to get the indigo.

Harvesting and processing

This is long hard work for the team, and eventually our truck is loaded up with as much indigo as we can fit in.

Now the indigo needs soaking in water for a few days, then the liquid needs aerating, alkalizing and then the beautiful deep, bright blue indigotin powder settles in the liquid, ready to be used.

I’m going to be having a lot fun with this.

I love this story, and I am very jealous of this experience :) I am surprised they didn´t know Indigo was a dye.

My parents travelled to Morocco in June. They saw indigo at a market and brought me some in rocks and powder form. I have been wondering if it´s real indigo or not, specially the powder has such a bright color that it doesn´t seem completely natural to me.

Do you know if there is some way to test if it´s natural or a synthetic imitation? (other than taking it to a laboratory).

i had a lot of fun reading about this (money bags malae!) ;)